Grant Writing #

This section is currently very UK-centric. We would welcome collaborators who can comment on other national and regional contexts.

This section addresses things you might consider when writing a grant, or planning a project from an internal budget. Our research cultures won’t change by themselves: we have to make it happen. By planning our projects responsibly now (rather than waiting for funders to ask for environmental impact statements), we can model the change we want to see in the world.

Key Recommendations

Researchers should include climate impacts in our funding applications. Where there is no dedicated section to do so, other sections (such as Justification of Resources and Data Management Plan) can be used as a workaround. Funders should update application processes to ensure the research they fund is aligned with climate targets. The timescale is tight, so projects already underway should also review their climate impacts (if this was not done at the application stage). The data, tools and skills to design climate optimal research is not yet widespread. Temporary suspension of carbon intensive activities is recommended as we build capacity.

Funding Landscape #

Writing in early 2025, our view is that:

- Requirements will change. The UK funding landscape is set to change, and researchers should collaborate proactively with funders to co-produce the next generation of funding allocation mechanisms.

- But we don’t have to wait. In the meanwhile, there is plenty of scope within existing funding application frameworks to propose sustainable research. For example in UKRI applications, the Justification of Resources and the Data Management Plan sections can be used to reflect on digital carbon and wider sustainability and justice issues.

- More transitional guidance from funders is welcome. Funders have signalled that they are open to existing frameworks and guidance being interpreted in this way. The authors of this toolkit welcome this, and invite funders to actively signal the direction of travel and the interim arrangements (especially to peer reviewers).

We need, urgently, to ‘green’ our research. This is a time of transition. The UK has declared a climate emergency, as have universities and research organisations across the sector. Major research funding bodies are prioritising decarbonisation, sustainability, and just climate transition. Use of Information Communications Technology (ICT) is widely recognised as a major source of carbon emissions.

However, with the exception of the Wellcome Trust, these funders are not yet explicitly asking applicants about the sustainability or climate justice dimensions of their projects. Revisions to application processes take time, partly because of justifiable concerns about making applications more onerous: increasing the work that goes into applications can have its own implications for equity and justice.

The Digital Humanities Climate Coalition supports the revision of funding processes to centre sustainability and climate justice. We also argue, however, that existing application frameworks can also accommodate sustainability and climate justice considerations. In this transitional time, these frameworks can be interpreted flexibly to provide reviewers with relevant information, so that they can favour sustainable research and reject unsustainable research.

Interpreting UKRI Environmental Sustainability Guidance for the Digital Humanities (2025) is a short guide published by the DHCC, consolidating some of the signals that UKRI and other funders have made that they support consideration of digital sustainability in funding applications.

The Planet Centric Design toolkit was created more for business and innovation contexts, but there are tools and exercises there that could be adapted either for bid development or for the early stages of a project.

Data Management Plans #

One area of special interest for this toolkit is the UKRI’s Data Management Plan (DMP). There are also opportunities to include information of this kind in the Ethics, Case for Support, and Justification of Resource sections. We recommend that you read this section in conjunction with the annotated DMP in ‘A Researcher Guide to Writing a Climate Justice Oriented Data Management Plan’, by the DHCC Information, Measurement and Practice Action Group.

A DMP outlines a project’s approach to managing data through a response to a series of prompts on data creation, storage, sharing, and ethics, which are provided in the application guidance. UKRI guidance also points researchers to resources they might find useful in preparing a DMP and encourages applicants to demonstrate knowledge of institutional policies and procedures. Some grant writers find the DMP useful since it tends to focus one on the minute material detail of the research process (exactly what data will be created, by whom, when, etc.). However, the DMP is sometimes handled by specialists who may not be closely involved in the project, and/or via templates or text that is copy-pasted and lightly edited.

Neither the DMP application guidance nor its associated assessment criteria currently explicitly refer to the climate crisis or environmental emergency. However, funders have indicated an openness to researchers proactively interpreting existing DMP guidance for sustainability and climate justice. Reading DMP guidance (e.g. in the AHRC Funding Guide) from a climate justice perspective makes it clear that its prompts are worded with sufficient openness that they enable researchers to respond in ways which align with sectoral and national climate commitments.

Five areas can be immediately considered when writing a DMP:

Energy proportionality. In the Royal Society’s report Digital Technology and the Planet (2020), a key principle of the chapter on Green Computing is ’energy proportionality’. For a researcher writing a climate justice-oriented DMP, the imperative here is not to produce numbers that show their anticipated energy use per month by some measure. Rather it is to demonstrate that the research design seeks to ensure that the resources used (e.g. hardware purchases, compute time, data storage) will be proportional to the results produced (e.g. outputs, anticipated findings, impacts). Minimal Computing approaches may be useful.

Resource proliferation. A key finding of The Shift Project’s report Lean ICT: Towards Digital Sobriety (2019) is that increasing the lifetime of professional laptops from 3 to 5 years could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 37%. Equally, recent and important long form studies like Kate Crawford’s Atlas of AI (2021) have underscored the ecological impacts of device proliferation. For a researcher writing a climate justice-oriented DMP, the imperative here is to justify the environmental costs of new device purchases, to demonstrate alignment with institutional policies on device recycling (e.g. does your institution follow or go beyond Waste from Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) regulations in their approach), and to consider and explain the benefits of using refurbished devices if appropriate. For example, if external hard drives purchased for a previous project and pooled by your research group are serviceable and within warranty, they may be perfectly usable for a future project that seeks to take a climate justice-oriented approach to data management, and can be described as such in your DMP.

Computationally intensive research. Computer time requires energy use. Lannelongue, Greanley, and Inouye give us tools to calculate this in their 2020 paper ‘Green Algorithms: Quantifying the Carbon Footprint of Computation’. In turn their ‘Green Algorithms’ service gives us an interactive way to understand this energy use relative to driving a car, taking a flight, or planting trees, a way – in short – of describing energy proportionality. For a researcher writing a climate justice-oriented DMP, the imperative here is to describe the decisions taken about the purchase of storage and storage services that relate to and overlap with computationally intensive research activities. For example, that the energy source mix for cloud providers have been investigated, or that data will be structured and stored in ways that reduce compute time and the need for brute force approaches.

Where measurement is challenging, err on the side of caution. Good quantitative data on environmental impacts can be hard to come by. Building capacity in this area is important. However, don’t be shy to make choices that appear more sustainable to you, even if their positive contribution is not quantified.

Identifying relevant standards, frameworks, and guidelines. There are by now many resources that support climate justice across many different aspects of project management. These range from guidelines to minimise the carbon footprint of events, to standards for stakeholder mapping and engagement, to database tools for estimating the carbon intensity of procurement decisions. There are also institution-level standards with project-level relevance (e.g. the Science Based Targets initiative, often referred to as SBTi). These all involve some form of data collection and management, and as such, the DMP is an appropriate place to include them.

These considerations fit within existing guidance. For example, the prompt that asks whether there are ‘any legal and ethical considerations of collecting the data’ (p. 56) raises the possibility of discussing the ethics of over-producing data that need energy and resources to be stored. Similarly, answers to the question ‘How long will the data be stored for and why?’ (p. 56) might reasonably balance long-term preservation of research outputs with the imperative to reduce the proliferation of data on public facing services that are unused for long periods. Finally, the requirement that the applicant and their institution have ‘considered all the risks, and storage will be in line with the institution’s data management policy’ prompts reflection on long-term data storage, the adaptations to climate change required to ensure long-term storage, and the entanglement of institutional data management policies with environmental strategies.

We recognise that not all researchers will have the knowledge and expertise to develop these lines of thinking and to make informed decisions. We are also mindful that researchers may wish to “play it safe” and not risk a bid by including climate justice-oriented practice that may be new to them. However, the scientific advice is clear that there is an imperative to act immediately.

We hope this short guide will enable researchers to be bold in interpreting the DMP guidance, rather than seeing climate justice-oriented actions as another box to tick. Climate justice-oriented data management practices can be threaded through the research programmes of all researchers applying for UKRI funding. There is nothing stopping us apart from developing our knowledge so we can define the appropriate actions to take.

The Data Carbon Scorecard may also be useful to apply. There are nine questions, each answered either green, amber, or red. The output is a score out of nine (lose one point for every red, half a point for every amber). For example, “Size of data asset is less than 2gb (green), 2-3gb (amber), more than 3gb (red).” And, “Data is batch processed (green), data remains static (green), data receives near real-time updates (amber), data received real-time updates (red).”

Suggested DMP Citation: Researchers who have referred to this guidance in developing a DMP may optionally include wording such as, "This DMP is aligned with Digital Humanities Climate Coalition's 2022 recommendations on data management and climate justice."

Should you footprint your project? #

"To give just one example, did you know that the very notion of a personal carbon footprint --- a concept that's completely ubiquitous in discussions about personal responsibility --- was first popularized by BP as part of a \$100 million per year marketing campaign between 2004 and 2006?" Tracing Big Oil's PR war to delay action on climate change Harvard Gazette, Geoffrey Supran, Sept 2021 (Accessed 4 April 2022)

It is not our responsibility, nor our priority, to directly measure the carbon impact of our research. Often we won’t even need to make precise estimates. However, we do all urgently need to develop a degree of carbon literacy, and carrying out footprinting exercises can be one great way to learn. Whether this is something you might do at the grant-writing stage, and/or include in the resources you are requesting to do on a funded basis, depends on your individual circumstances.

Labos 1point5’s GES1point5 and the Thoughtworks Cloud Carbon Footprint are examples of carbon footprinting tools (for labs and for cloud usage respectively); The DIMPACT tool estimates emissions associated with audiovisual streaming and other digital activities; the GHG Protocol also offers various tools. The Carbon Ladder is a tool written from a Knowledge Management perspective, and the associated Data Carbon Scorecard is a relatively light-touch tool that may help you to plan a new project. For estimating the embodied carbon of devices, Quantis’s Product Attributes to Impact Algorithm might be used. The Software Carbon Intensity Specification is designed to score a software system’s carbon emissions. Tools like Website Carbon Calculator and Ecograder can estimate a website’s carbon impact.

The desire for precise data can sometimes be counterproductive. Rough qualitative understandings are often enough to help us make sustainable decisions. Decisions that may initially require research can become fast, easy and intuitive over time. “Is doing it this way more or less carbon intensive than doing it that way? Are they in the same ballpark, or completely different orders of magnitude? Is the intuitive approach OK here, or do we need to assess this more rigorously?”

One useful concept here is Emissions Factors (EF). Put in simple terms, an EF gives a sense of how carbon intensive something usually is. The IPCC maintains a database of EFs. In the UK, the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy provide spreadsheets which include Emission Factors. By multiplying the values listed there with your own “activity data” (for example, financial spend, or miles travelled in a car, or tonnes of plastic waste disposed, etc.) you can generate an estimate of the carbon impact. For power draw from the grid, they suggest a blanket 213g CO2 equivalent per kWh. However, a tool like Carbon Intensity can help to drill down into the details, providing a regional estimate based on what plants are actually generating electricity.

However, definitive EFs are often not available for the type of activities that, as researchers using digital tools, we may want to know about. Thoughtworks’s Cloud Carbon Footprint estimates emissions based on data centre billing data in four usage categories: Compute, Storage, Networking and Memory (RAM). It is partly based on Etsy’s EFs (called the Cloud Jewels).

Another useful resource is the SustainableIT.org Resource Center, a curated library of models, frameworks, calculators, templates, glossaries, and governance guidance focused on responsible and sustainable IT and AI. It includes a reference model and maturity model for IT-led sustainability, ESG metrics taxonomies, an emissions calculator spreadsheet, a strategy toolkit, a lifecycle-based AI sustainability runbook, data governance principles, leadership frameworks, and signposts to standards and best practices, aimed at corporate IT leaders operationalise sustainability across digital systems.

We are currently in an interim period, during which the data, skills and tools for sustainable decision-making are built and shared. But we do not have to decide now, once and for all, how research will be conducted in the future. It would be irresponsible to continue to emit on the basis of business-as-usual as we scope, gather data, and build capacity. We therefore recommend active advocacy and community-building, and the bold use of moratoriums on carbon intensive activities.

Publishing and archiving #

There are complex questions around what to keep and how to keep it. There are a few suggested resources in the Working Practices section of this toolkit.

Travel and catering #

Travel and catering may also be important to consider at the grant-writing stage. The short version is to fly less and to serve plant-based food. There is further information in the Working Practices section of this toolkit.

Innovative approaches to innovation #

Funding bodies generally like innovation. So why not include experiments in sustainability in your project proposal, in areas such as publishing, archiving, storage, signage, communication, travel, food, events, activities, physical materials, locations and places, lighting, heating and cooling, aesthetics, resource sharing, moratoriums, or whatever else you can think of?

[Climate-KIC](https://www.climate-kic.org/ is a large network across Europe focused on climate innovation. EdgeRyders’s [https://edgeryders.eu/t/the-future-of-ecological-urban-living/12097](The Future of Ecological Living) is filled with interesting and provocative suggestions in a variety of domains.

Choosing research questions #

It is important to adapt our research methods to make them less carbon intensive, and to improve our awareness of our environmental impacts.

But can we also corral our research communities to more directly investigate environmental issues? For example, humans interact with and through Information Communication Technology (ICT) in unpredictable ways; “how ICT changes consumer behavior … seems to be an underexplored, but essential aspect of the causal mechanisms that have to be understood for predicting the environmental impact of digitalization” (Bieser and Hilty 2018). A literature review carried out by Freitag et al. (2021) found no strong consensus about the future of ICT carbon footprints, including “disagreement” whether or not

- energy efficiencies in ICT are continuing

- energy efficiencies in ICT are reducing ICT’s carbon footprint

- ICT’s carbon footprint will stabilize due to saturation in ICT

- data traffic is independent of ICT emissions

- ICT will enable emissions savings in other industries

- renewable energy will decarbonize ICT.

Another literature review on remote working only weakly confirmed the ‘common sense’ view that remote working saves energy; 26 of 39 studies suggest that it does save energy, however “differences in the methodology, scope and assumptions of the different studies make it difficult to estimate ‘average’ energy savings” (Hook et al. 2020).

More broadly, climate change gives rise to a variety of political, ethical, and philosophical issues. Within the arts and humanities, these have long been the concern of the environmental humanities, and fields like the Digital Humanities have plenty to explore in terms of the cultural construction of technologies (everything from email to Bioenergy Carbon Capture and Storage), and the use and interpretation of data and models.

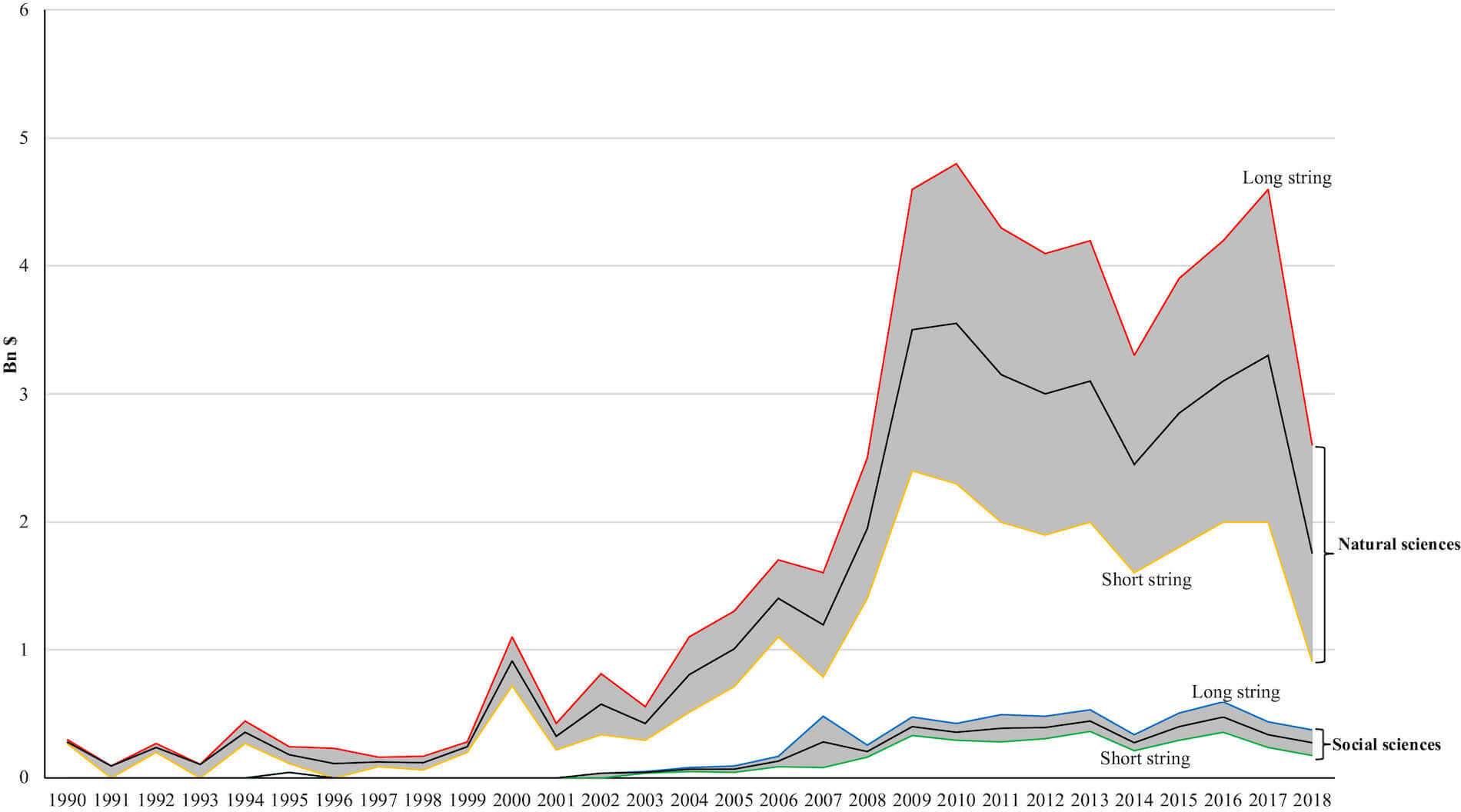

However, climate research funding has heavily favoured the natural sciences (see figure). “Limiting global warming to 1.5°C will require rapid and deep alteration of attitudes, norms, incentives, and politics.

Some of the key climate-change and energy transition puzzles are therefore in the realm of the social sciences” (Overland and Sovacool 2020) — we can also add, the realm of the arts and humanities.

Funding for climate research in the natural and technical sciences versus the social sciences and humanities (USD). The gray areas represent ranges of estimates derived from short and long search strings. Src: Overland, Indra, and Benjamin K. Sovacool. ‘The Misallocation of Climate Research Funding’. Energy Research & Social Science 62 (April 2020): 101349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101349.

Further reading #

Juckes, Martin; Pascoe, Charlotte; Woodward, Lucy; Vanderbauwhede, Wim; and Weiland, Michele. 2022. ‘Interim Report: Complexity, Challenges and Opportunities for Carbon Neutral Digital Research’. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.7016952.

Juckes, Martin; Bane, Michael; Bulpett, Jennifer; Cartmell, Katie; MacFarlane, Miranda; MacRae, Molly; Owen, Alex; Pascoe, Charlotte; Townsend, Poppy; ‘Sustainability in Digital Research Infrastructure: UKRI Net Zero DRI Scoping Project Final Technical Report’. 2023. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8199984.

Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. 2021. ‘Greenhouse Gas Reporting: Conversion Factors 2021’. 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/greenhouse-gas-reporting-conversion-factors-2021.

Baker, James; Ohge, Christopher; Otty, Lisa; Walton, Jo Lindsay (eds.), ‘A Researcher Guide to Writing a Climate Justice Oriented Data Management Plan’. 2022. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6451499.