Advocating within your institution #

Knowledge will never be able to

replace respect in man’s dealings

with ecological systems.

— Roy Rappaport, quoted in Steward Brand’s Cybernetic Frontiers (1974)

Put your institution in context #

Our institutions are taking action. Most European universities have now set net zero targets and milestones, as part of broader sustainability strategies. They are integrating climate risks and opportunities into governance and strategy, and embedding climate change across their curriculums. Within institutions like these, advocacy is not about putting climate change on the agenda.

Despite this, the Higher Education sector is not where it needs to be. In ten points, here is our view on the state of the sector in 2023. This is based on conversations rather than rigorous analysis. But they should be enough, if you work at a Higher Education Institution, to get a rough sense of where your institution is at.

- Comparisons are hard right now. Net Zero target dates are not easily comparable across different institutions because of different methodologies and assumptions. League tables are challenging to assemble. Interpreting your institution’s ranking requires careful research. The EAUC’s Standardised Carbon Emissions Framework has recently been released.

- Definitions matter. The terms ‘carbon neutral’, ‘climate neutral’, and ‘Net Zero’ tend to mean different things (and also get defined in different ways). Make sure your institution’s commitment covers Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 emissions.

- Pathways matter. Emissions en route to Net Zero are as important as the Net Zero date itself. It is vital to make as much progress as early on as possible. Make sure your institution has ambitious milestones along the way. If bringing your Net Zero date forward is challenging, you may find more traction bringing forward milestones.

- Offsets are problematic. Net Zero poses significant greenwashing temptations, especially around the use of carbon offsetting. Not all offsets are equal, and institutions are taking very different approaches to them, and to what counts as an ‘unavoidable emission.’ Make sure your institution also sets an Absolute Zero target date.

- Benchmarks are seldom science-based. Institutions naturally tend to pick their Net Zero dates by asking, ‘What is feasible for us, given our business model, and given what others in the sector are doing?’ But to have a good chance* of achieving 1.5 degrees, global emissions need to roughly halve by 2030, and reach Net Zero by 2050. Global North countries have ethical and practical obligations to reach these milestones even sooner (e.g. China’s current Net Zero date is 2060, India’s current Net Zero date is 2070).

- SBTi are pretty busy right now. The Science-Based Targets initiative has yet to expand its work to universities, but a few universities are nonetheless aligning themselves; all should do so. Additionally, some universities that aim (and claim) to be SBTi aligned are not aligned with the latest recommendations. SBTi themselves are under significant pressure to water down their approach to carbon offsetting. The Alliance for Sustainability Leadership in Education (EAUC) is working on implementing SBTi principles in HEIs.

- Institutional policies and messaging are often inconsistent. If you work for a relatively well-resourced institution in the Global North, it needs to be achieving Net Zero well ahead of the planetary target date (2050) to be consistent with a 1.5 degree target. Some institutions have arguably already reached Net Zero.

- Implementation details are being worked out. Many institutions have Net Zero commitments that they do not yet know how to deliver. There is a risk of backsliding as the challenges and costs emerge.

- Risk management is unreflective of the scale of climate crisis. There are opportunities to realise more co-benefits across sustainability and risk management. Some traditional risk management methodologies may not really be suitable for dealing with climate crisis (e.g. around “deep uncertainty” and “tipping points”). Adaptation needs to be transformative.

- Don’t expect an even picture throughout the institution. In particular, many larger universities have decentralised governance structures, and different parts of the university may be very out of step with each other.

“A good chance”: There is intrinsic uncertainty in climate science modelling. Things may be better or worse.

Move your institution in the right direction #

Advocacy will look different in different institutions. It may often involve:

- Visibility and accountability. Building coalitions and keeping sustainability and climate justice high on the agenda. Holding the leadership and other internal stakeholders accountable.

- Translation for decision-makers. Working to make sustainability and climate justice expertise more legible within business cases and institutional strategy.

- Translation for stakeholders. Interpreting and curating your institutions’ targets and methodologies and making them more accessible.

- Up-to-dateness. Making sure that institutional strategy keeps evolving, given the rapidity with which climate issues evolve. Reviewing sustainability strategies and actions in light of the latest science and policy.

- Diving into complexity. Scrutinising more opaque areas such as procurement, pensions and endowments.

- Tools. Scrutinising the methodologies and assumptions embedded in your institution’s sustainability tools. Creating accessible and open source alternatives to commercial tools and knowledge bases.

- Anchoring. Strengthening your institution as a green ‘anchor institution’ within the local economy and community. Creating collaborations and synergies, both inside and outside your institution.

- Sectoral work. Sharing best practice across the sector, or questioning the framings that are common across the sector. For the UK context, the Accelerating Toward Net Zero report is useful background.

- Revolutions. Exploring possibilities for more radical, innovative, and disruptive approaches.

- Just being you. For example, using your expertise, e.g. as an arts and humanities researcher. To some extent this may already be assumed by institutional strategy.

Get involved in supply decisions #

When it comes to choosing suppliers, university workers may feel like we have our hands tied: by IT Services policies, procurement policies, long-term contracts arranged before our arrival, or even larger structures like procurement consortia or legal frameworks.

When universities work with external suppliers, pros and cons are often checkboxed via a procurement policy or requirements analysis process. This can constrain and limit open-ended learning and innovation — and ‘bake in’ the carbon and ecological consequences of existing, and already centrally paid for, ‘institutional’ digital infrastructures. Opaque supply chains and use of subcontracting (and sub-subcontracting, etc.) can make procurement decisions difficult to interpret.

Procurement decisions can be highly technical, and procurement teams typically seek expertise across the university. Sustainability is also written into procurement teams’ work, and there may be opportunities to clarify sustainability aims to centre climate justice and rapid transition based on the most up-to-date climate science.

HESCET helps to estimate the carbon intensity of procurement decisions, but in its current basic form it has quite a few limitations. It is based on a financial spend multiplied by a standardised Emission Factor, so it doesn’t automatically reflect things like “We got a special deal and bought twice as much for the same price,” or “We spent more because we chose a more sustainable supplier.”

Some procurement-related links:

- Hack Education: The history and future of educational technology

- Southern Universities Purchasing Consortium

- North Eastern Universities Purchasing Consortium

- UK Universities Purchasing Consortia partnership

- EAUC Scope 3 Working Group

- Spend Matters

- A 2022 Jisc report on digital sustainability contains a section on procurement, highlighting resources and organisations including the Higher Education Supply Chain Emissions tool (Scope 3 assessment based on Emissions Factors databases), Advanced Procurement for Universities and Colleges (for Scotland), WorldWatchers, carbon accounting software CO2Analysis, and supplier questionnaires from SupplyShift.

Approved supplier lists can also take decisions away from researchers. You may have someone who you know would be good to work with, but you need to get them on the approved suppliers list. This may take a prohibitively long time, or may get blocked altogether. It is easy to get discouraged. However, researchers should avoid pushing responsibility onto techs or sysadmins, and engage actively in discussion to find workarounds and push for change.

Or if you are the one who is making a decision? It is also worth remembering that rules don’t have to be followed.

Suggested Reading: Although it is not specifically focused on technology or sustainability, Moten and Harney’s The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study is a thought-provoking read about what it means to work ethically within the constraints of academia today.

Empowering Procurement #

Procurement teams are almost certainly thinking about sustainability and requiring suppliers to meet various criteria, but there are opportunities for collaboration to ensure that they are asking questions based on the most recent evidence.

For example, try to work with your Procurement and IT departments to extend the lifespan of devices (through extended warranties, prioritisation of repairability, workshops on device maintenance, repair cafes, pooling resources, etc.).

Energy Procurement #

Green tariffs are not straightforward. They push the energy market in the right direction, but energy that comes from the grid is currently supplied by a mixture of renewable and non-renewable sources, whoever your energy supplier is. Multi-year power purchase agreements (PPAs) supporting renewable investment should be used. Also check out the 24/7 Carbon Free Energy Compact. The safest way for your institution to really control its carbon footprint would be to generate all its energy on-site from renewable sources. Short of this ideal, an institution can generate some of its energy on-site, and develop battery storage, to help reduce power draw from the grid (especially when demand is high). Institutions can also explore better scheduling of energy intensive activities.

Procurement Law #

At time of writing in late 2022, UK procurement law is set to be reformed, and there are opportunities to pressure legislators to ensure it is fit-for-purpose. The response to the government’s Green Paper by the UK Universities Purchasing Consortia noted that universities incorporate social value into tenders, but did not extensively thematise sustainability or decarbonisation. It is important that any new legislation give institutions the flexibility to prioritise sustainability in procurement decisions, and ideally that it requires procurement in alignment with climate commitments.

Question the Cloud #

For many of its users, the public cloud is invisible infrastructure, barely noticeable except when it breaks. The Green Grid is an industry consortium focused on data centre energy efficiency and sustainability, and a gateway to a variety of research and resources. Thoughtworks’s Cloud Carbon Footprint is a promising-looking open source project for estimating the carbon footprint of data centre usage. The Climate Neutral Data Centre Pact is a voluntary initiative in support of the European Green Deal. The GEC has produced some guidelines for procurement teams to grill cloud providers.

When a university or other institution procures data storage and computing power, this is an opportunity to improve our own environmental impact, and to incentivise much larger players to improve theirs. Currently public cloud services are dominated by Amazon, Google, and Microsoft. Hyperscale datacentres have clear potential to achieve greater sustainability through economies of scale. Furthermore, running a data centre or a server with a low utilisation is typically less efficient, since there is an “overhead” to having it switched on in the first place (better one data centre at 100% than two equivalent data centres at 50% each).

At the same time, these also three companies deeply structurally and culturally committed to expanding the role of digital technology in everyday life, including the use of carbon intensive Machine Learning, whose green claims have been heavily dependent on carbon offsetting. The three cloud giants have also been criticised for their lack of transparency: there is a lot going on in those data centres that we don’t know about. In recent years, there has been something of a backlash against the public cloud as a sustainability panacea. See for example the Dark Matter Episode ‘The Cloud Fugitive.’ Some large companies are bringing workloads that used to be done on the public cloud back onto their on-premise infrastructure.

Here are just a few questions that might help get the conversations started, both internally with procurement teams, and externally with potential suppliers.

| Question | Notes |

|---|---|

| What are the broader climate policies of the provider (not just the cloud / data centre parts of its business)? | Greenpeace recently explored the green claims of AWS, Google and Microsoft. All three companies are pursuing decarbonisation and at the same time researching AI to support fossil fuel extraction. |

| What are the broader ESG policies of the provider? | ESG = Environmental, Social, Governance. ESG has its drawbacks, since it is rooted in risk management. If a company has outward impacts which are damaging to the environment, but which are unlikely to pose the company any reputational or legal risk, then those impacts might not negatively impact their ESG ratings. |

| What is the data centre’s PUE, CUE, and WUE? | In areas where electricity is cheap, there may not be strong incentives to use it as effectively as possible. The Power Useage Efficiency metric is widely used in the data centre industry, to express how much of the total energy the data centre uses is used in its computational processes, rather than ancilliary processes such as cooling (1.0 would be a perfect score). It does have its limitations (see e.g. Clouded II documentary). Carbon Useage Effectiveness and Water Useage Effectiveness are complementary metrics. None of these metrics can tell us whether the renewable energy used for the data centre could be put to better uses. |

| What is the average localised carbon intensity of electricity powering your data centre(s), for all regions you propose to deliver the service? | Renewable energy claims can used “market-based” accounting or “location-based” accounting. Market-based approaches can contain useful information, but by themselves they are misleading. Ideally you want both. See if you can get data for the past few years. Make sure you figure out the role of carbon offsets. |

| What ecolabels or certifications apply to the buildings of the data centre? | E.g. Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM), ENERGY STAR, Green Star, Comprehensive Assessment System for Building Environmental Efficiency (CASBEE), the DGNB System, Green Globes, HQE, ISO 50001, Superior Energy Performance, etc. |

| What is the data centre’s carbon footprint? | It is important to pressure Cloud providers to be ever more transparent about the carbon footprint (and other environmental impacts) of their activities. Keep in mind that purchasing a Cloud service often won’t mean access to one data centre only: you can ask about the provider’s entire portfolio of data centres, as well as the specific resources that will be fulfilling your requirements. |

| What methodologies are used to calculate carbon footprint and other environmental impacts? What types of uncertainty are present in this data? | Some uncertainties may be impossible to eliminate, but it is good to identify them (and in some cases it may be possible to quantify them). Ask about market-based and location-based carbon accounting. Ideally it’s good to have data from both methods. |

| What are the company’s decarbonisation targets? What steps have been taken and will be taken to reduce the CO2e emissions associated with the cloud services being tendered? | |

| Does the company purchase Renewable Energy Certificates, and/or use Power Purchase Agreements? How about 24/7 hourly matching? | |

| To what extent does the provider use carbon offsetting? | Carbon offsetting should be avoided as much as possible. The planet’s capacity to offset emissions is limited. The remaining carbon budget is tiny, and the strongest moral and pragmatic claims to that budget lie in the Global South. Ask about Beyond Value Chain Mitigation. |

| Is the data centre’s excess heat redistributed to the district heating network? | Heat may also be captured and used in other ways, i.e. as a supplemental power source. Heat re-use in itself is a good sign, although as a rule of thumb, it might also correlate with situating data centres near denser populations where there is more need for scarce renewable resources … so it is complicated. |

| What are the other local energy needs? | Where the data centre is sited, If the data centre wasn’t using the energy, who would be using that energy? |

| How much electricity does the data centre generate from on-site renewables? | |

| Was there opposition to the siting of the data centre from local stakeholders, and how was it resolved? | |

| How is the data centre integrated into the local community now? | |

| What is the data centre’s water usage like? | You can ask about WUE for example. |

| What jurisdiction is the data centre in? | |

| What is the data centre’s exposure and vulnerability to physical climate risks? | For example, proximity to flood plains. |

| What climate and ESG-related standards and certifications does the provider use? What forms of independent verification are used? | See [Rina Diane Caballar, ‘Tougher Reporting Mandates Ahead for Data Centers’ (Data Center Knowledge, 2023)] (https://www.datacenterknowledge.com/regulation/tougher-reporting-mandates-ahead-data-centers) |

| What is the provider’s view of the robustness and comparability of their competitors’ carbon disclosures? | For example, Google claims to be carbon neutral (based on offsetting), but it’s complicated. |

| Find some tricky questions. Or if you can’t, ask them to describe what most challenges or bewilders them. | Try to engage the providers as real people in the complexities of climate transition. |

| Especially where big tech is concerned, how does the provider encourage us to imagine the future in certain ways? | Amazon, Google, Microsoft et al. don’t just influence the future via their policies, but also through their cultural influence. As arts and humanities scholars, we are well-placed to start conversations around this. |

| What is the procurement team’s scoring methodology? What proportion is devoted to sustainability, and how has this been derived? | Procurement decisions take place in legal frameworks, although they can of course voluntarily go beyond these in securing appropriate suppliers. |

Doing it ourselves? #

There are very significant economies of scale associated with data centre operation. There is generally now little gained from locating data centres closer to users, as edge computing has solved latency issues for most use cases. So for many universities, outsourcing makes sense. However, there are many factors to bear in mind. If you’re in an area where energy is already very green, switching from a small local data centre to a cloud solution could increase your carbon footprint. Public cloud solutions also create various incentives and affordances that may or may not benefit sustainability, some of which are explored in the 2022 documentary Clouded: Uncovering the Culture of the Cloud. Universities also frequently operate their own small on-prem data centres for resilience.

Data centres can be integrated into local heating infrastructure e.g. the supercomputer LUMI’s “waste heat will account for about 20 percent of the district heating in the city of Kajaani” (Jakobsson 2021). The University of Edinburgh is home to the Advanced Computing Centre at Easter Bush, near Edinburgh. It provides HPC and data services to academia and the private sector. It is currently part of a pilot study for a novel geobattery technology for recycling heat from cooling facilities (Fraser-Harris et al. 2022).

Climate change is also associated with deep uncertainty, and tail risks — e.g. political instability or legal / regulatory change where data is housed, the security of optical fibre cables — can legitimately inform decision-making. Methodologies are becoming more available (e.g. Cloud Carbon Footprint) for monitoring on-premise data usage. Universities have strong and distinctive relationships with the public sector, and are used to cross-sectoral collaboration.

There may also be complementarities with on-site renewable energy generation. Although trying to compete directly with Amazon or Microsoft is probably not a good idea, we should remain open-minded, creative and bold in our approach to data storage and computation resources.

For provocations and inspirations around server autonomy, see Syster Server and Full Stack Feminism. And here’s a short article arguing for data centre decentralisation, with many smaller data centres located near their renewable power sources such as solar and wind.

Further reading

Christopher Tozzi, ‘Just How Green is Your Cloud Migration?’ (Data Center Knowledge, 2023)

The Cloud as a factory? #

In ‘The Cloud is a Factory’ (2021), Nathan Ensmenger argues that framing the Cloud as a factory helps us to:

- “Restore a sense of place to our understanding of the information economy”;

- “Appreciate the importance of infrastructure” including the Cloud’s consumption of water and electricity and its need for “roads and bridges and sewer systems”;

- “Recognize the fundamental interconnectedness (and interdependencies) of all of our infrastructures” and use this as a critical lens on technological hype;

- Consider the supply chains of hardware and elements such as lithium, tin, cobalt, and rare earths, and the “set of stories to be told about global politics, international trade, worker safety, and environmental consequences”;

- Identify the effects or lack of “compensatory benefits in terms of jobs, tax income, or the development of new infrastructure” that may come from establishing a data centre; and

- “Consider the changes to work that the Cloud enables in other industries,” for example autonomous vehicles. (Mullaney et al. 2021)

Ask questions #

Of course you will do what you can in areas where you have discretion. But what is the best way to connect with more senior decision-makers? Some institutions are more democratic than others, some leaderships are more accessible than others. If you do feel cut off, a simple rule of thumb is to show up to all available events where senior management may be present, and make sure that pertinent questions are being asked. Ideas for questions include:

- What are the climate risks and opportunities associated with x?

- Has x been carbon footprinted? Why or why not?

- What data is available and/or desirable to assess the climate-related risks and impacts of x?

- What sustainability data and/or analyses have been generated in relation to x? Do we know how much these outputs are being used? How can they be made more useable?

- Whose infrastructure is being used? Is it clear where responsibility for emissions begins and ends?

- Can our climate ambition be raised?

- Can our Net Zero date be brought forward?

- Can we rely less on carbon offsets?

- Is x compatible with our sustainability strategy?

- Is our risk appetite in relation to x appropriate, given our sustainability strategy?

- Is x compatible with our mission statement and values?

- How does x advance our sustainability strategy?

- Our sustainability strategy says x. Are the implications compatible with our mission statement and values?

- Is our Net Zero strategy compatible with limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees, given disparities in global capacities to reach Net Zero?

- How have we assessed the risk of missing our Net Zero milestones, and what is being done to mitigate this risk?

- How can sustainability work be better resourced and rewarded in all roles throughout the institution?

- How is the institution’s business model transforming in response to physical and transition climate risks and opportunities?

- How can we realise co-benefits between our sustainability strategy and other agendas within the institution?

Find your internal collaborators #

If you’re not already familiar with your institution’s governance structure, check online for information on your executive leadership groups and other key boards, committees, teams, and individual roles. The names and functions of things vary from institution to institution. For a university, some key roles / bodies / terms to explore include:

- Sustainability team

- Chief Sustainability Officer

- Chief Risk Officer

- Heads of Schools

- Vice Chancellor

- Students Union

- Union

- Audit committee

- Procurement team

- Senate

- Reporting requirements group

- Certification and compliance

- Health and safety team

- Business continuity

- ITS

Find your external collaborators #

Although this section of the toolkit is focused on advocating within your institution, a lot of it may also apply to how you work with partner organisations on research projects, to support them to develop and deploy digital tools in sustainable ways. For example, DH professionals at universities often work with arts, culture, heritage, and creative industries organisations. Here are a few tools and talking points:

- International Energy Association reports and Our World in Data’s CO2 and Greenhouse Gas emissions provide some useful high-level context - decarbonising the digital is important and urgent, but we should also make sure we keep things in proportion (and don’t miss out on easy, impactful actions outside of the digital).

- Julie’s Bicycle has lots of resources for arts organisations especially (not just focused on digital sustainability).

- The Networked Condition is a project about “the environmental impact of the creation and delivery of artworks using digital technology,” including a carbon calculator.

- Sustainability: A Surprisingly Successful KPI.

- Joe McGrath, ‘Cost as a Proxy for Carbon: The Inconvenient Truth’.

- From the Green Software Foundation, The Green Software Maturity Matrix is a self-assessment tool for organisations to “understand the extent to which they have implemented green principles, patterns, and processes for building and operating their software systems.”

- TOSS is a work-in-progress (as of 2024) from the Green Software Foundation which focuses on organisational change, and seeks to “describe a framework incorporating a method that is focused on a decision tree approach. It would also reveal where voids exist, providing ideas for future initiatives.”

- Carbon Literacy Project offer a variety of sector-specific Carbon Literacy Toolkits.

- Digital Decarbonisation, Data Carbon Scorecard is a lightweight tool for quickly evaluating the potential carbon impacts of a new data related project

- Proposal for a Technology Carbon Standard.

- Of course, the digital is not the enemy of the sustainable. Digital technology has a huge role to play in a rapid and just climate transition. Rasoldier et al. (2023) offer some thought-provoking questions we can use to scrutinise the promised benefits of digital innovation.

Find levers to drive change #

What are the next big digital infrastructure decisions being made within your institutions and are environmental concerns being taken into account? Explore where the decisions are being made, establish collaborative relationships across the institution, and plug into new sources of information. Things may work differently in theory vs. practice, so conversations can be important to build an understanding of how things have been decided in the past.

Sometimes it may be easier to realise impact in less obvious places. Even a committee that does not have climate as part of its core remit still has sustainability and climate risk responsibilities, and will still be making decisions that have implications for your institution’s carbon footprint, climate risk management, and climate justice impact.

Confront greenwashing and discourses of delay #

Most of us are, thankfully, long past the point where our institutions won’t even think about climate transition. But we are still in an era of greenwashing and discourses of delay. These are not always cynically motivated: often they arise through misplaced optimism.

In 2009, TerraChoice conducted market research on existing products which made ‘green marketing’ claims. Their ‘Seven Sins of Greenwashing’ are still relevant to conducting and communicating research for tomorrow:

- The hidden trade-off. Saying something is green by using narrow criteria and ignoring other more important environmental impacts.

- No proof. Claiming greenness without easily accessible supporting information.

- Vagueness. Using poorly defined terms, often for marketing or reputational purposes.

- Irrelevance. Committing to a valid environmental claim, but an unimportant or resolved one.

- Lesser of two evils. Making true claims within your own category, which distract from greater concerns of the category as a whole.

- Fibbing. Making environmental claims that are false.

- Worshipping false labels. Giving the impression of 3rd-party endorsement when the association does not in fact exist.

We have come up with seven more:

- “I can’t bear to look!” Greenwashing by omission. An institution may drag it’s heels on collecting sustainability data or doing rigorous analyses, especially if deep down it knows it might not like what it will find.

- Transparency without agency. Even if an institution is being honest, rigorous and bold in how it collects and analyses sustainability, and how it communicates the results … is it checking to make sure this information is actually being used? Is it supporting the creation and empowerment of audiences and users?

- Passing the buck. Similarly, an institution may disclose climate-related information in the expectation that key stakeholders (students, funders, regulators, the public, etc.) will then take appropriate action, and alter the institution’s operating environment.

- Convenient benchmarking. It’s natural for organisations to benchmark themselves against similar organisations (e.g. a university will tend to compare itself to other universities in the same country, and perhaps regionally and globally). This can lead to an “eco echo chamber” where entire sectors are behind on climate ambition. Science-based targets are one good antidote, although here too we’ll have to be careful – science seldom speaks with one voice, and there may be temptations to cherry-pick the most convenient advice.

- Sustainability as an excuse for every decision. If sustainability is not the real driver behind a decision, it is better to be honest about that. If there are incidental sustainability benefits, that’s great, but frame them appropriately. Otherwise you risk giving the wrong impression about the sustainability costs and benefits of various actions.

- “A+ for effort, but …” Some initiatives really do contribute in positive ways, but use up significant amounts of time, energy, attention, money and other resources which could be much better used. Should we think of them as a form of greenwashing? Maybe. Of course, we can’t always expect to be perfectly efficient when it comes to climate action. But if the 2020s is to be the decade of delivery, we can’t have (just for example) sustainability leads being asked to devote large amounts of their time to raising awareness with symbolic actions.

- “It’s ALL just greenwashing!” Of course, it is also possible for something to look like greenwashing, when it is actually making a useful and well-proportioned contribution to climate transition. Better to be constructive and detailed when assessing an initiative, than to make accusations based on a hunch.

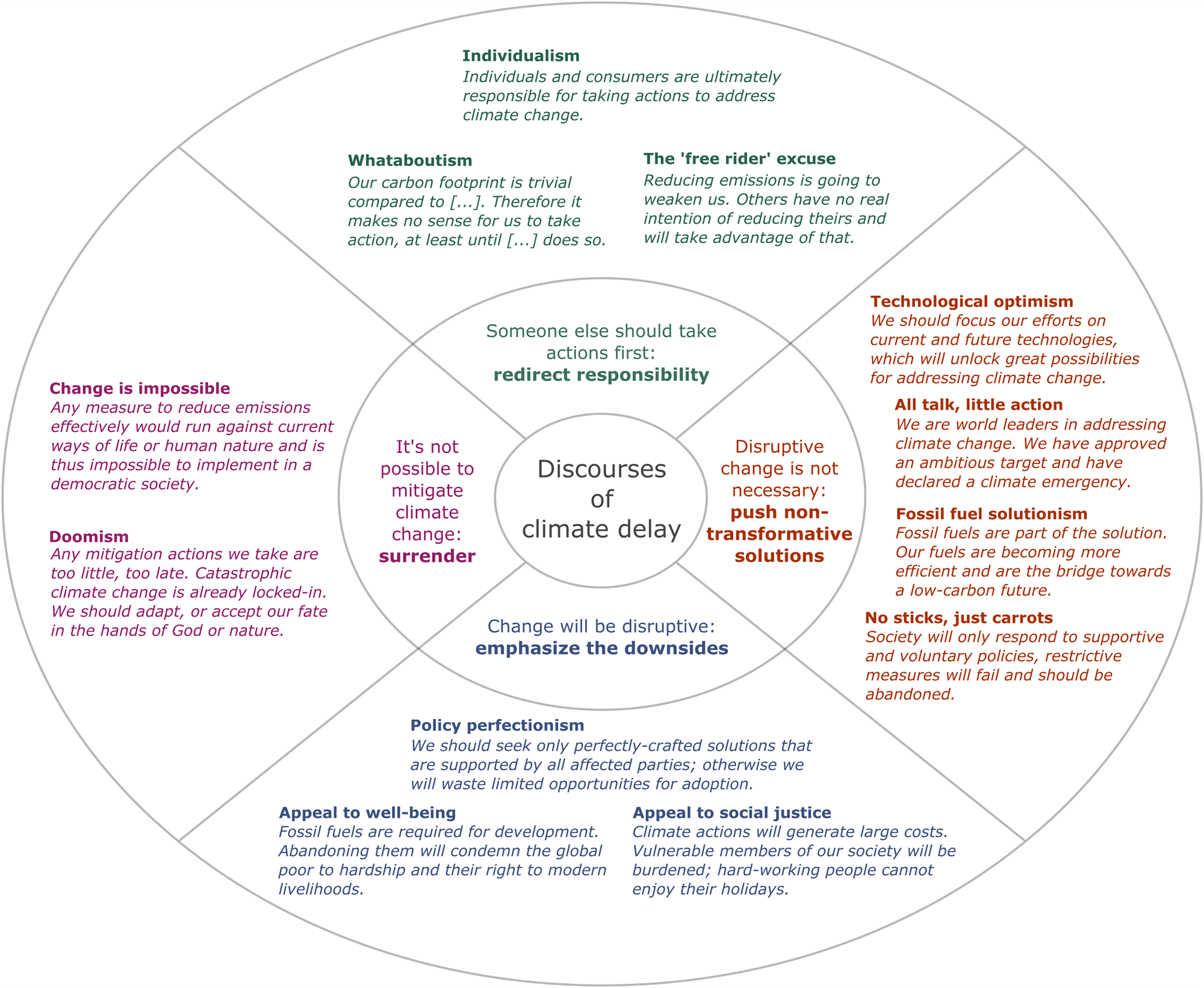

Lamb et al. (2020) mention climate denialism, climate-impact scepticism, ad hominem attacks on climate scientists, but devote most of their article to “discourses of delay.” They offer this typology:

The incentives to greenwash or to delay are set to rise as the global economy decarbonises. As the false forest begins to sprout around us, how do we make sure we don’t get lost in it? There are no easy answers, but this certainly seems to be a space where the arts and humanities can usefully intervene through research, education, and activism. Close reading of green claims, distant reading of large corpori, collaboration with cultural heritage institutions and other trusted sources of information, and innovative approaches to cultivating truthfulness in the public sphere.

Confronting green colonialism and green extractivism #

Broadly speaking, it is communities in the Global South who are most exposed to the impacts of climate change. At the same time, climate change mitigation can be done in ways that disadvantages Global South actors, and reinforces or recreates colonialist power hierarchies.

“The European Green Deal also ignores the environmental impact of Europe’s drive for renewable energy and electric mobility on other parts of the world, where resources for this economic shift will have to be extracted,” writes Myriam Douo. A 2024 blogpost by Andreea Belu analyses how the policy narrative around “twin transition” (digital transition and green transition) has shifted to emphasise securitisation and defense.

Techno-optimism #

“Solutionists deploy technology to avoid politics; they advocate ‘post-ideological’ measures that keep the wheels of global capitalism turning.”

Techno-optimism could be seen as a form of greenwashing, or a discourse of delay, but it also deserves its own special category. It is of special significance to arts and humanities researchers who work on and with technology (e.g. the Digital Humanities).

Techno-optimism in relation to climate change means putting disproportionate trust in Negative Emissions Technologies, geoengineering, or other emerging or proposed technologies, that either (a) are unproven; (b) are unproven at scale; (c) have potential negative side-effects; (d) have potential negative implications for climate justice; and/or (e) are dependent on political, social and economic conditions in ways that might reasonably undermine their benefits.

Undue support for technological solutions can undermine carbon emissions reduction (things we know will work: reducing energy consumption, switching to renewals, and leaving unburnable fossil fuels in the ground).

Here are a few angles on techno-optimism, including pointers to where to find out more. Note also the cluster of related terms: techno-optimism, techno-utopianism, techno-solutionism, techno-fixes.

- It is useful to historicise emerging climate technologies and energy technologies. One recent history identifies an “overall dynamic which should give climate scientists and policy makers pause for thought before pursuing yet another round of technological promises without social transformation in the hope of averting dangerous climate change” (McLaren and Markusson 2020).

- After Geoengineering (2019) by Holly Jean Buck is a sympathetic-but-critical exploration of climate engineering technologies. It emphasises how such technologies might have very different impacts on the climate depending on how they are governed, and in whose interests.

- In Experiment Earth: Responsible Innovation in Geoengineering (2016), Jack Stilgoe writes, “My aim in this book is to draw attention away from risk assessment towards uncertainties: the things we don’t know, that we can’t calculate and that may remain incalculable.”

- Geoengineering Watch is a campaign site with an emphasis on Solar Radiation Management.

- Science and Technology Studies and feminist philosophy of science explore the intersection of science, power, knowledge, and culture. E.g. Flegal (2018) takes an STS perspective on solar radiation management, to explore what enables “debates about the management of the representation of a technology which does not yet exist” (Flegal 2018).

- Indigenous knowledge offers a rich variety of alternatives and critiques to dominant forms of technoscience.

- Using the language of uncertainty can be a good way to move beyond a crude pro-tech vs. anti-tech impasse. Uncertainty is part of all good science. Often uncertainty can be quantified in ways that are useful for decision-making. Some uncertainty (sometimes described as “deep uncertainty”) is difficult or impossible to quantify or model, but can still be factored into decisions made about technology.

- Epistemological Luddism See

- Langdon Winner’s 1977 Autonomous Technology

- Steven E. Jones, Against Technology: From the Luddites to Neo-Luddism (2006)

- Lachney and Dotson’s 2018 ‘Epistemological Luddism: Reinvigorating a Concept for Action in 21st Century Sociotechnical Struggles’.

- Conviviality is an approach to technology Ivan Illich’s 1973 Tools for Conviviality. Illich’s approach is based around building tools that improve autonomy, and he seeks to understand autonomy in a relational and egalitarian way. Vetter (2018) explores links between conviviality and degrowth.

- Questions. Stephanie Mills’ Turning Away from Technology (1997) includes a useful list of ‘78 Reasonable Questions to Ask About Any Technology’ (findable online tool). For example, “Does it preserve or destroy biodiversity? Does it preserve or reduce ecosystem integrity?”

- Don’t Look Up (2021) is a movie about science communication and techno-optimism.

- Some climate-related techno-optimism is not about decarbonisation directly, but rather about the use of Artificial Intelligence to squeeze more efficiency from constrained resources, and/or develop deep adaptations for a much less hospitable climate. The overlapping fields of Critical Data Studies, Critical Internet Studies, Critical Algorithm Studies, Critical Digital Studies, and Science and Technology Studies more broadly, offer useful perspectives on AI imaginaries. Arts and humanities researchers can play a role in interrogating the hopes invested in AI, as well as in its development, deployment and governance.

Build your own legitimacy within your institution #

Get in rooms where decisions are made and, where appropriate:

- Appeal to transparency. The operational methods which management uses to make resourcing and strategic decisions is crucial but it is even more crucial that these methods and decisions are being talked about outside of the managerial circles – for accountability and trust.

- Appeal to the institution’s values, as expressed in its value statement, mission statement, vision statement, and/or existing strategy documents. It is likely that these will use the language of environmental sustainability. (If they don’t, this in itself is something to be addressed urgently).

- Appeal to collaboration and interdisciplinarity. Climate transition is incredibly complex, and nobody has the full picture.

- Appeal to reputation. Reputation is hugely important to many universities. (At the same time, reputational risk does not fully capture the ethical imperative to decarbonise and work for climate justice).

- Appeal to the risk cascades. Climate change does not sit demurely in a box all by itself. If climate action is being weighed against some other priority, think about the ways the two things are already connected. Climate risks transmit into financial risks, reputational risks, etc.

- Appeal to life and death. Be gentle. Be collaborative. Don’t alienate the people you hope to persuade. But sometimes conversations about governance and strategy can get tangled up in a very financial way of thinking, where everything is ultimately reducible to budgetary implications. Is the real reason universities are decarbonising because they are concerned that low climate ambition will affect student satisfaction scores, recruitment rates, and therefore revenue? No, that doesn’t tell the full story. We know that a just climate transition is about far more than that.

Advocate for small changes #

Even small changes add up. Are you aware of any policies or common behaviours at your institution which might be generating unnecessary carbon? For example: pictures attached to your signature for marketing purposes, or sharing email attachments back and forth when shared cloud documents are available to you and your colleagues.

When advocating for smaller changes, be sure to focus on easy wins and changes which support a general shift in attitude and attention. Use small changes to prefigure larger changes, to raise awareness, and to address feelings of powerlessness. If a small change would involve constant disproportionate effort, or encourage policing of behaviours, it’s probably not a good candidate to focus on. Use small changes to make your institution a better place overall. Use small changes to help people feel good about climate action.

Further reading: In Praise of Smaller Actions.

Advocate for big changes #

We are all susceptible to dissonant reasoning (see the sections below on greenwashing and discourses of delay). Climate change means big changes are coming (and are already taking place), yet it is easy to imagine that the situation is more stable and constrained than it actually is. We should look beyond existing business models and business cases, beyond existing institutions and social orders, and beyond merely incremental changes. Within our institutions, we can support and encourage each other to always think and act more boldly.

Connect small changes and big changes #

As arts and humanities researchers, we have our own special ways of connecting smaller changes with wider issues. The technical systems we move through are filled with many inefficiencies that could be addressed by better design; these can also be opportunities to think about deeper system change. For example, one archivist for a FTSE100 company started looking into her company’s preservation workflow:

it soon became clear that literally everything produced by the company was being saved in a range of locations by a range of people across these servers. Even items transferred and already stored on the archive servers were being stored on other department (and personal) drives, leading to copies of some documents reaching double figures. (Williamson 2021)

And one Twitter user has this beautiful confession:

Hello, my name is Graeme, I have a PhD in computing, and I am a senior accessibility consultant, but when I want to type “é” on a Windows laptop I go to Beyoncé’s Wikipedia page and copy/paste the letter from there.

Why do we sometimes play media we are not even paying attention to? Does our operating system or browser make it easier to use Google Search, download and overwrite a file, rather than remember where we saved it on our hard drive? Why do we unintentionally end up with multiple versions of the same file on our hard drives? The structures we occupy create incentives and affordances. Working to transform these, at every level from the structures of a particular user interface, to the structures of extractivist capitalism itself, can help us to develop a “holistic understanding of behaviour that bridges the ‘individual’ and ‘systemic’” (Newell et al., 2021).

Here are a few ways that the ‘smaller’ things we do in our teaching and research might inform our wider advocacy, both within our institutions and beyond.

- “Work as if you lived in the early days of a better nation,” as Alasdair Gray wrote. Remember that individual agency and systemic change are connected. When our colleagues or students bring up a very good question, “How much difference can the individual make?” it can be helpful to reframe the ‘individual’ as an ‘early adopter,’ or ‘co-producer’ — someone who goes against the grain of existing systems, and/or tries out prototypes, to help new systems emerge.

- Capture your experience as useable information. When you adopt other environmentally conscious behaviours, note wherever you experience friction with the systems you inhabit. Capture this precisely (a challenge in itself). Use it to advocate for changes (big and small). Reflect on what general lessons might be drawn (and share these). You may wish to explore UX concepts such as choice architecture, choice editing, dark patterns and green patterns.

- Engage students as researchers. Consider incorporating similar challenges into your teaching and assessment. Give students the resources to recognise the energy impact of their digital activities, and ask them to journal where there may be opportunities to redesign the systems they’re operating in, inspired by minimal principles. You might frame this as auto-ethnography.

- Widen the conversation. Exploring the redesign of systems to support behaviour change is useful in itself, and easily links to exciting topics across a wide range of fields: minimal computing, sustainable software design, UX design, speculative design, critical media studies, Science and Technology Studies, critical algorithm studies, political economy, psychology, economics, cultural studies, systems thinking, and more. It can also be a way into big questions around the role of technology in climate transition. What are the limitations and risks of techno-fixes? Why can’t we simply design our way out of climate crisis? Might critical design thinking nonetheless inform campaigning and activism?

- Perhaps we should redesign design too? When should we prototype, test, and iterate, and when might other approaches be appropriate? When should we accept a workaround, and when should we devote resources to solving something ‘properly’? Can we do more to get things right the first time (or at least after fewer iterations), or build in safeguards so that issues which emerge during testing fall within known parameters? Can we better manage technical debt?

Further reading #

“Maladaptive responses to climate change can create lock-ins of vulnerability, exposure and risks that are difficult and expensive to change and exacerbate existing inequalities”. IPCC report of Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. The latest IPCC report explained in under 7 minutes.

Arora, Saurabh, Barbara Van Dyck, Divya Sharma, and Andy Stirling. 2020. ‘Control, Care, and Conviviality in the Politics of Technology for Sustainability’. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 16 (1): 247–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2020.1816687.

Bassett, Caroline, Ed Steinmueller, and George Voss. 2013. ‘Better Made Up: The Mutual Influence of Science Fiction and Innovation’. Nesta Working Paper.

Berkovich, Izhak, and Lotem Perry-Hazan. 2022. ‘Publicwashing in Education: Definition, Motives, and Manifestations’. Educational Researcher, January, 0013189X211070810. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X211070810.

Bove, Tristan. 2021. ‘Techno-Optimism: Why Money and Technology Won’t Save Us’. Earth.Org. 8 June 2021. https://earth.org/techno-optimism/.

David Devins, Jeff Gold, George Boak, Robert Garvey and Paul Willis. 2017. ‘Maximising the local impact of anchor institutions: a case study of Leeds City Region’. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Doyle, Joseph, and Donal O’Mahony. 2014. ‘Nihil: Computing Clouds with Zero Emissions’. In 2014 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Engineering, 331–36. Boston, MA: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/IC2E.2014.65.

Edwards, Carlyann. 2022. ‘What Is Greenwashing, and How Do You Spot It?’ Business News Daily. 2022. https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/10946-greenwashing.html.

Flegal, Jane A. 2018. ‘The Evidentiary Politics of the Geoengineering Imaginary’. UC Berkeley. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4887x5kh.

Freitas Netto, Sebastião Vieira de, Marcos Felipe Falcão Sobral, Ana Regina Bezerra Ribeiro, and Gleibson Robert da Luz Soares. 2020. ‘Concepts and Forms of Greenwashing: A Systematic Review’. Environmental Sciences Europe 32 (1): 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-0300-3.

Steven E. Jones, Against Technology: From the Luddites to Neo-Luddism (Routledge, 2006)

Lachney, Michael, and Taylor Dotson. 2018. ‘Epistemological Luddism: Reinvigorating a Concept for Action in 21st Century Sociotechnical Struggles’. Social Epistemology 32 (4): 228–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2018.1476603.

Lamb, William F., Giulio Mattioli, Sebastian Levi, J. Timmons Roberts, Stuart Capstick, Felix Creutzig, Jan C. Minx, Finn Müller-Hansen, Trevor Culhane, and Julia K. Steinberger. 2020. ‘Discourses of Climate Delay’. Global Sustainability 3. https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2020.13.

McLaren, Duncan and Nils Markusson. 2020. ‘Guest Post: A Brief History of Climate Targets and Technological Promises’. Carbon Brief. 13 May 2020.

McLaren, Duncan, and Nils Markusson. 2020. ‘The Co-Evolution of Technological Promises, Modelling, Policies and Climate Change Targets’. Nature Climate Change 10 (5): 392–97. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0740-1.

Meagan M. Ehlenz. 2018. ‘Defining University Anchor Institution Strategies: Comparing Theory to Practice. Planning Theory and Practice’. 19, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2017.1406980

Miller, Jack. 2020. ‘Climate Change Solutions: The Role of Technology’. UK Government. House of Commons Library. 24 June 2020. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/climate-change-solutions-the-role-of-technology/.

Miller, Sebastian. 2017. ‘The Dangers of Techno-Optimism’. Reviews. Berkeley Political Review. 16 November 2017. https://bpr.berkeley.edu/2017/11/16/the-dangers-of-techno-optimism/.

Mullaney, Thomas S., Benjamin Peters, Mar Hicks, and Kavita Philip, eds. 2021. Your Computer Is on Fire. Cambridge, Massachusetts ; London England: The MIT Press.

Nemes, Noémi, Stephen J. Scanlan, Pete Smith, Tone Smith, Melissa Aronczyk, Stephanie Hill, Simon L. Lewis, A. Wren Montgomery, Francesco N. Tubiello, and Doreen Stabinsky. 2022. ‘An Integrated Framework to Assess Greenwashing’. Sustainability 14 (8): 4431 https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084431.

Powell, Alvin. 2021. ‘Oil Companies Discourage Climate Action, Study Says’. Harvard Gazette (blog). 28 September 2021. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2021/09/oil-companies-discourage-climate-action-study-says/.

Quoquab, Farzana, Rames Sivadasan, and Jihad Mohammad. 2021. ‘“Do They Mean What They Say?” Measuring Greenwash in the Sustainable Property Development Sector’. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 34 (4): 778–99. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-12-2020-0919.

Sarah Knuth, Brandi Nagle, Christopher Steuer, Brent Yarnal. 2007. ‘Universities and Climate Change Mitigation: Advancing Grassroots Climate Policy in the US. Local Environment’. 12, 5. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830701657059

Stilgoe, Jack. 2016. Experiment Earth: Responsible Innovation in Geoengineering. London New York: Routledge.

Vetter, Andrea. 2018. ‘The Matrix of Convivial Technology – Assessing Technologies for Degrowth’. Journal of Cleaner Production 197 (October): 1778–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.195.

Walton, Jo Lindsay. 2022. ‘A Greenwashing Glossary’. 2022. https://medium.com/@jolindsaywalton/a-greenwashing-glossary-4cf0ccf92476.

Walton, Jo Lindsay. 2022. ‘Bitcoin and Stone Money: Anglophone Use of Yapese Economic Cultures, 1910-2020’. Finance and Society 8 (1): 42–66. https://doi.org/10.2218/finsoc.7126.

Winner, Langdon. 1977. Autonomous Technology: Technics-out-of-Control as a Theme in Political Thought. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.